Photo: John Schaidler, Unsplash

The New FoRB Axis: Pluralist vs. Anti-Pluralist

That the world is changing; few dispute this anymore. How it is changing, or whether it is for the better or worse, that is a fierce debate. Fareed Zakaria calls it an Age of Revolutions. Matthew Kroening calls it The Return of Great Power Rivalry. Michael McFaul makes a version of that same argument in Autocrats vs. Democrats. Robert Kaplan, somewhat pessimistically, calls it a world in permanent crisis, a Waste Land. The Germans, always good for a long word for a hard topic, call it a Zeitenwende, a watershed, a moment of change. One could add another, krisenbilder, an overlapping series of crises. Alternatively, we could default to the most common historical metaphor that has emerged, as well summarized by David Sanger in his book, New Cold Wars.

But however many bestsellers and geopolitical bumper stickers we slap together, one significant assumption is shared in common: the old, American-led postwar order is under stress, and the fractures are beginning to show. How, I wonder in a longer article for The Review of Faith & International Affairs, should we reconceive of freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) under these revolutionary circumstances?

Let me set the table with two assumptions before making the argument.

First, the major powers in international relations are all, to one degree or another, rediscovering different forms of national identity or what could be, if ambiguously, called nationalism. Whether it is President Trump’s America-First, or Modi and the BJP’s soft-Hindutva, Vladimir Putin’s Russkiy mir, Xi Jinping’s Confucian-Communist fusion, or the European challengers—Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Georgia Meloni in Italy, Viktor Orban in Hungary, or Alice Weidel of Germany’s AFD—the resurgence of some form of nationalism in international relations now seems well documented. That there is almost always a significant religious-cultural component to this resurgence—Peter Mandaville refers to it as “The Religious Turn in Great Power Politics”—will necessarily require our attention.

Second, this is taking place as American power and influence are, in relative terms, at least on the decline. This is not simply a recent result of the so-called isolationist faction in America’s Republican Party, but an economic and geopolitical trend that has stretched over decades. Whether one optimistically describes it as the rise of the rest, as Fareed Zakaria does, or calls it a new multipolarity, the fact is that while American power in absolute terms may be stable and growing, the rest of the world is growing and exerting itself at a faster and more aggressive pace still. The relative gap remains very wide, but it is narrowing, not widening.

Some would prefer that this geopolitical snapshot be shortened simply to bipolarity or a cold war. There is a security argument for this that looks more directly at actual geopolitical and economic parity, in which there is only one real clear challenger: China. Iran, irascible as it may be, and Russia, belligerent spoiler that it is, are not in any reasonable estimate challengers to American supremacy. The European Union could be, and perhaps if it is pressed into self-sufficiency, it may someday be, but for today, it most certainly is not. Military strategists are likely correct in making this argument, and if this were a paper about military balance, I would defer to their analysis. However, this is an argument about diplomacy, and for that reason I prefer to talk more about great power rivalry rather than the bipolarity of a new cold war. Where human rights are concerned the size and scale of hard power is, while not irrelevant, less absolute.

It is into these assumptions about the world order that I reintroduce our question: should our, and here I broadly mean the Western world, diplomacy on FoRB change to better suit these emerging conditions? And what would those changes be?

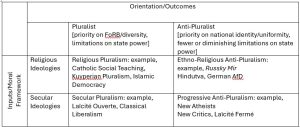

What I called the religious problem in world affairs almost a decade ago has been well described by scholars like Jonathan Fox as a secular-religious competition. This framing continues to strike me as constructive, but I think our changing geopolitical conditions call for a new axis to consider FoRB. I call this the pluralist/anti-pluralist competition.

This shifts or at least augments the current religious vs. secular debates about state pluralism to a somewhat more pragmatic approach. Rather than framing debates on the basis of inputs as ideologies of religion or secularity, it frames the problem by way of the orientation or outcomes. It is more consistent, perhaps, with Charles Taylor’s argument that we think pluralism “has to do with the relation of the state and religion; whereas in fact it has to do with the (correct) response of the democratic state to diversity.”

In my article in The Review of Faith & International Affairs I argue that there are two main anti-pluralist challengers today: progressive anti-pluralism, and nationalist anti-pluralism. While these approaches seem opposite to many on the Western political spectrum, they both in fact support the use of political power to inject a form of anti-pluralism into the political sphere. I argue that they could, therefore, be considered more alike than they are different. They further have a kind of symbiotic horseshoe relationship: fear of the other anti-pluralism tends to drive more extreme versions of their own anti-pluralist tendencies. Further, I argue that emerging geopolitical shifts in the world suggest that progressive anti-pluralism is generally on the decline, whereas nationalist anti-pluralism is ascending.

For those with an interest in promoting pluralist politics generally and FoRB specifically, this suggests the need for a shift not in conviction, but in intellectual and diplomatic approach.

Here I find the new concept of covenantal pluralism especially relevant because it not only invites political engagement with the full weight of (secular or religious) conviction (contra progressive anti-pluralism), but it also therefore is able to propose indigenous and often-religious rationales for limitations on political power (contra nationalist anti-pluralism). As world politics shifts to more nationalist anti-pluralism, the answering call from covenantal pluralism is not to expunge this newly dangerous religion from the balance sheet, but rather through convicted engagement to demonstrate new—and in many cases retrieve the old—indigenous political-theological rationale for limitations on state power. Freedom of religion or belief itself is perhaps the most profound such limitation, and the world’s great religions and great civilizations are hardly without the substantive moral and theological language to buttress this bedrock of pluralist politics. But our intellectual and diplomatic approach in the years ahead may look less legal, less economic, less pragmatic, and more historical, more religious, and more theological.

Perhaps, the time of the technical economists and the political scientists (those skilled in social contracts) is passing for an age, and the time of the historians and the theologians (those skilled in crafting social covenants) has come again.

* This article is adapted from Robert J. Joustra, “Freedom of Religion or Belief amid Great Power Rivalry: Geopolitics and the Future of FoRB Scholarship and Strategy,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 23 (4) (Winter 2025): 57-75.